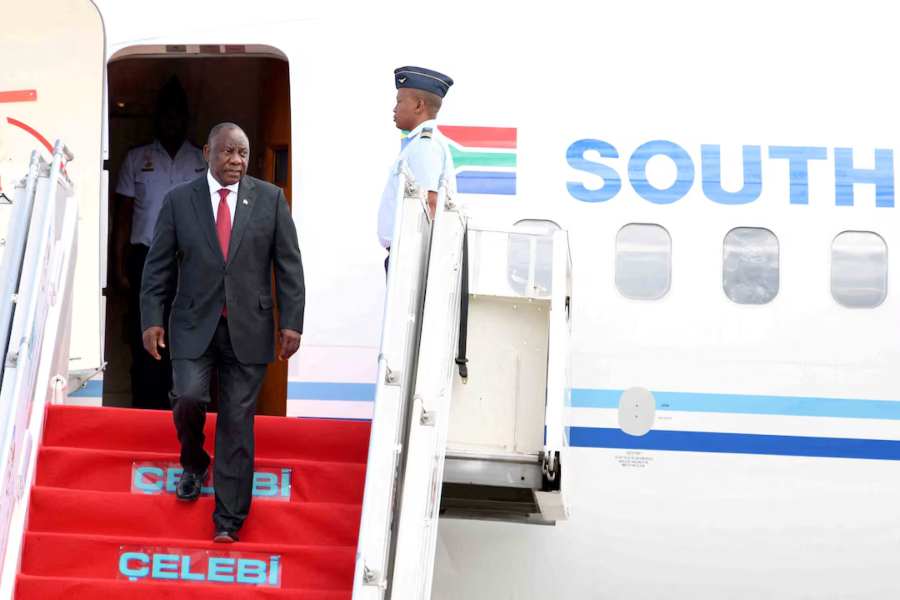

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa said Thursday he wants to strike a “meaningful deal” with former U.S. President Donald Trump to ease escalating tensions between the two nations, triggered by disputes over land reform and South Africa’s genocide case against Israel at the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

Speaking at a conference organized by Goldman Sachs in Johannesburg, Ramaphosa responded publicly for the first time to Trump’s recent executive order cutting U.S. financial assistance to South Africa. The aid suspension came after Washington criticized Pretoria’s approach to land redistribution and its legal case against Israel, a close U.S. ally.

“We don’t want to go and explain ourselves,” Ramaphosa said. “We want to go and do a meaningful deal with the United States on a whole range of issues.” The president said he hoped diplomatic tensions would subside and that South Africa could work toward restoring relations with the U.S. through direct engagement. While he did not offer specifics, Ramaphosa said the proposed deal could involve discussions on trade, political relations, and international diplomacy. “I’m very positively inclined to promoting a good relationship with President Trump,” he added.

Earlier this month, the Trump administration announced an executive action to reduce aid to South Africa, citing disapproval of its domestic and international policy choices. Chief among U.S. concerns is South Africa’s ongoing land reform program, which seeks to redistribute land—often without compensation—as part of efforts to correct historical injustices from the apartheid era. Additionally, South Africa’s decision to bring a genocide case against Israel to the ICJ has further strained relations. The case, filed in January, accuses Israel of committing genocidal acts during its military operations in Gaza. The move has drawn global attention and has been criticized by Washington as politically charged and hostile toward a U.S. ally. In response, the Trump administration characterized South Africa’s stance as undermining shared diplomatic goals and aligning against Western interests in international legal forums.

While U.S. aid to South Africa does not represent a major portion of the country’s overall budget, officials in Pretoria are increasingly concerned about potential consequences for trade. Specifically, there are fears that South Africa’s eligibility under the U.S. African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) could come under review. AGOA grants duty-free access to the U.S. market for a range of African exports, providing substantial economic benefits to South African industries, particularly automotive, agriculture, and textiles. Any threat to this preferential trade status could jeopardize jobs and investments. Analysts warn that AGOA has historically been used as a strategic policy tool by U.S. administrations and may be leveraged further amid mounting geopolitical disagreements. “Ramaphosa’s call for a deal is likely aimed at de-escalating tensions and protecting economic interests,” said a Johannesburg-based political analyst. “But it will require careful diplomacy, especially given the polarized environment in both capitals.”

South Africa has maintained a policy of non-alignment in global conflicts, seeking to balance its relations with Western powers such as the United States while also deepening ties with China, Russia, and fellow BRICS nations. However, its ICJ filing against Israel has been interpreted by some observers as a tilt away from the West. Ramaphosa dismissed such interpretations, reiterating his commitment to peaceful dialogue and multilateralism. “We are not trying to antagonize anyone,” he said. “Our actions reflect our commitment to international law and justice.” South African officials have defended the ICJ case as a moral imperative in the face of humanitarian concerns. Yet, the move has undoubtedly complicated Pretoria’s relations with Washington at a time when global diplomatic divisions are intensifying.

Despite the fallout from the executive order, Ramaphosa remains hopeful that a reset is possible. He indicated a willingness to visit Washington in the future to discuss areas of mutual interest and rebuild trust. “I want the dust to settle,” Ramaphosa said. “And then, we must move forward.” Whether the Trump administration will reciprocate remains unclear. Trump has historically responded favorably to leaders who pursue direct negotiations but has also imposed punitive measures on countries he perceives as opposing U.S. interests.

For now, Ramaphosa’s comments signal an attempt to stabilize a key bilateral relationship at a time of heightened global uncertainty.